Wouldn’t it be great if we understood why humans do the things we do? We are a decidedly unpredictable bunch, and most of the time we’re not even sure why we’ve done things ourselves. Why on earth, for example, did I spend three hours looking at subscription boxes online yesterday? (Actually, if you read to the end of this article, you’ll be able to suggest a few answers to that.)

This inherent unpredictability can make second-guessing user behaviour in mobile apps seem like a pretty daunting task, and yet understanding your users and anticipating their actions (and reactions) is exactly what it takes to make an app business a success. Rather than launching into trial-and-error changes to move your metrics on user engagement and conversion, approaching apps from the user’s perspective is the smart way to ensure that you’re delivering what they really want - whether or not they know it themselves.

But how do you make that happen? Thankfully, social and behavioural psychology can offer some answers: below are five psychological theories that can be applied easily and effectively to improve an app’s chances of success.

1. Choice Paralysis

Case Study: Choice paralysis has been made famous by Barry Schultz’s Choice Paradox, based on research affectionately known as ‘the jam study’. In this experiment, shoppers were shown a table with 24 varieties of jam on it, and those who sampled them received a coupon for $1 off any jam. On another day, shoppers were shown a table with only six varieties of jam. The large display attracted more interest than the small one, but people who saw the small display were ten times more likely to buy than those who saw the large display.

Applying It To Apps: Obviously, a certain amount of choice is necessary: no one likes being told what to do. But too much choice means that we avoid making a choice at all. Remember my hours spent looking at subscription boxes? Faced with all those options, I didn’t sign up to any them. Limit the options being offered to users and, as well as receiving better overall uptake rates, you’ll be able to focus more on optimising the options that are given. Using A/B testing allows you to see how altering the number of choices and the way that they’re presented can have a significant impact.

2. Random Rewards

Case Study: B. F. Skinner’s experiments are amongst the most famous in behavioural psychology, and his theories on variable schedules of reinforcement are put into practice by countless businesses. In one of Skinner’s experiments, treats were released when a pigeon pecked at a sensor, but the frequency at which the treats were given was random. Surprisingly, this made the pigeon peck more than if the frequency was regular. Not convinced? The exact same principle is applied to most gambling machines: the promise of rewards combined with the inability to predict when they will be given increases desire and engagement.

Applying It To Apps: Giving rewards can seem like a no-brainer - who doesn’t like being rewarded? We’re hardwired to seek them out, thanks to the sense of achievement they give us and our natural competitive spirit. However, if rewards are given too often they lose their novelty, and users will stop putting effort into earning them. Surprising a user with a discount offer or exclusive access builds anticipation for more offers that could follow, and so makes them more likely to stick around. The real knack to improving customer retention rates is to give these rewards at random - with no clear way to directly earn them, users are encouraged to keep engaging until it happens again.

3. Incomplete = memorable

Case Study: Few people have heard of the Zeigarnik Effect, but we’ve all seen it in action. Psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik noticed that waiters could remember details of the orders for tables they were serving, but only until the customers had paid. Once the task was considered completed, the details were forgotten.

Applying It To Apps: Use our natural instinct to work towards completion by making elements feel like they’re part of a process, or as if they’re building towards a final goal. A good example that you’ve probably clicked your way through before is the two-step sign up process. The user clicks on a button or a link, and in order to get where they want to go they have to fill out a sign up form that pops up. Seems simple, but because the user has initiated an action, they’re more likely to fill out the sign up form in order to finish it. That said, drawing a process out too long risks losing the pull of completion - as with the idea of ‘flow’ below, the action needs to have a clear and achievable objective for a user to engage with. Another great use of this principle is in re-engagement: reminding lapsing users of an action they left uncompleted has a good chance of drawing them back to the app.

4. Flow.

Case Study: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi proposed the Flow Model to explain the sensation of concentration and productivity we experience when we’re fully absorbed in a task. If you’ve ever looked up from an activity and realised that time has flown without you realising it (in my case, three whole hours), then you’ve experienced ‘flow’. Studies carried out with thousands of participants have found that flow most commonly occurs when people are actively engaged in a task, rather than at times of leisure. There seems to be a sweet spot where the level of challenge is balanced with the individual’s skill level, meaning that both frustration and boredom are avoided.

Image from UXDesign.

Applying It To Apps: To maximise time spent in an app, users need to feel engaged but not overwhelmed. If an app is too straightforward or simple, people will lose interest; if it’s too complex, they will become anxious. Examine your app analytics to see where users are spending the most time, and therefore are most likely to be experiencing flow, but also to find the moments that are disrupting it. Having a complex feature introduced before users have developed enough knowledge of the app to deal with it could be blocking flow.

5. Reciprocity Principle

Case Study: In his 1971 ‘soda study’, Dennis Regan asked participants to undertake a selection of tasks with a partner - who was really his research assistant, Joe. During the tasks, some were given a soda by Joe, and others were not. At the end of the experiment, Joe asked them to buy a raffle ticket from him. Those who had been given a soda earlier on were far more likely to buy a ticket.

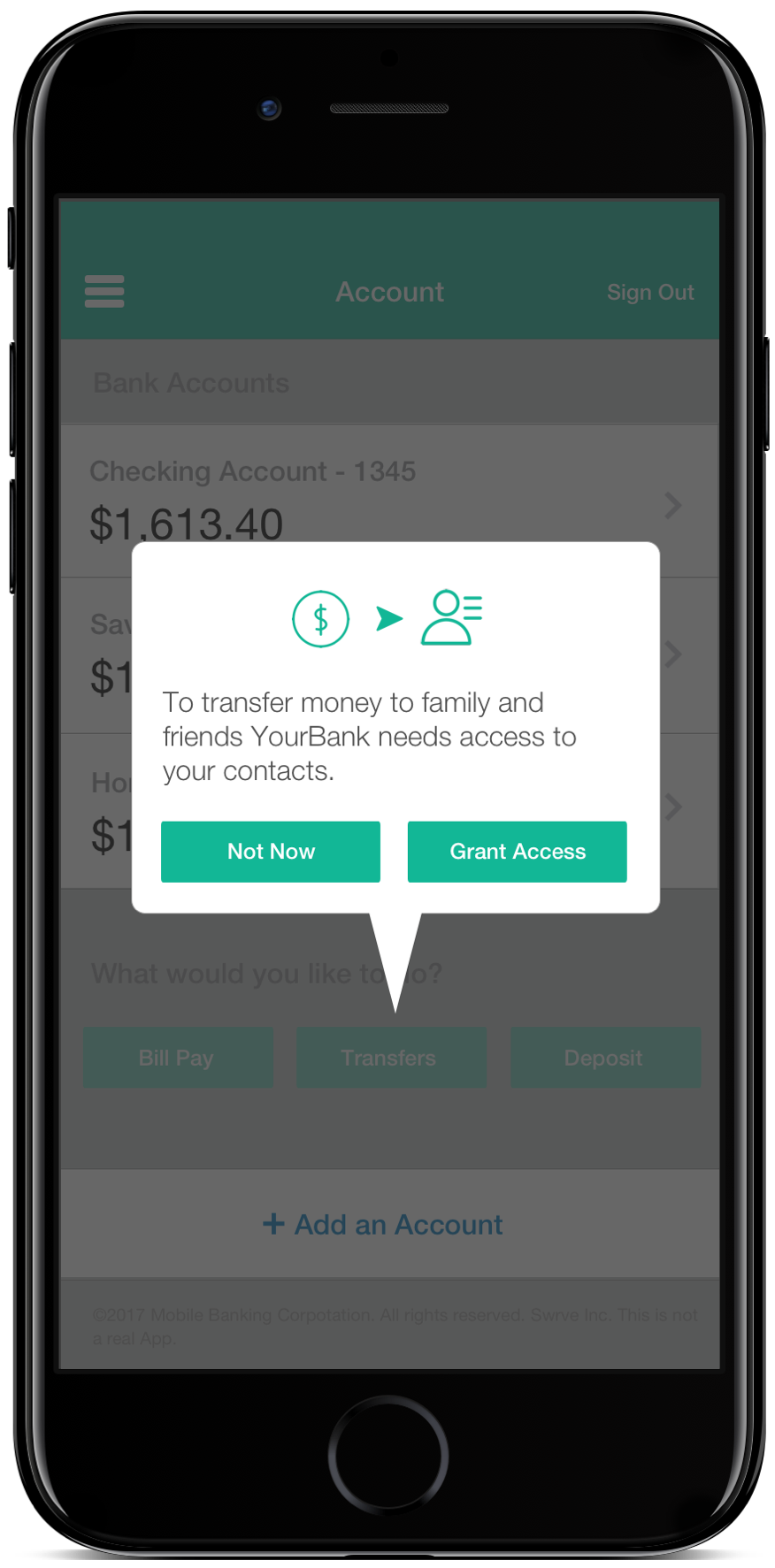

Applying It To Apps: It’s a social norm to respond to a positive action with another positive action: you get the first round of drinks in, and I’ll get the second. In terms of apps, this can mean giving to a user before you can take from them. Allowing users to see the value of the app first makes them more likely to submit their details and create an account, or to give approvals for location access and push notification opt-in. Asking for this information only when it’s necessary, and therefore when it seems logical to say yes, means that it seems like a small favour to ask in order for the app to do work for the user.